Natural Variability, Attribution and Climate Models #1

Examples of Changes in Droughts and Floods before Climate Change

In the last set of articles we’ve looked at past trends in extreme weather, following the flow of chapter 11 from the 6th assessment report of the IPCC.

How do we know the cause of any changes?

In recent years in most of the media everything that changes is “climate change” which is implicitly or explicitly equated with burning fossil fuels, i.e., adding CO2 into the atmosphere. It’s a genius catchphrase from a marketing point of view, not so helpful for scientific understanding.

I used to prefer the term “anthropogenic global warming” but it has its flaws as well, as some recent trends are believed to be anthropogenic but not from adding CO2 into the atmosphere. An example is changes that result from reduced aerosols in the atmosphere as a result of burning less biomass.

I’ll generally try and stay with “anthropogenic” or “from more CO2”, but there’s no copy editor, so let’s see.

Lots of changes in past climate metrics are simply natural variability. Understanding and quantifying natural variability is a big topic and our knowledge is always going to be imperfect.

For example, there were multi-decadal megadroughts in North America and Europe in the past 1000 years. They were probably “unprecendented” for their time, but clearly weren’t caused by burning fossil fuels.

Here is a reconstruction of the drought index over 1000 years of western North America from Aiguo Dai 2010 - a low value is bad:

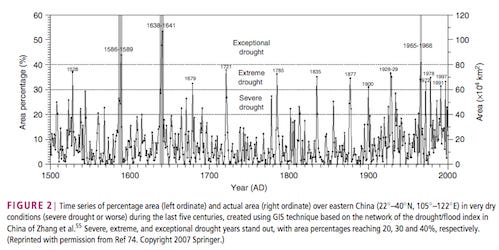

And 500 years from China - a high number is bad, as this is area in drought:

Here’s another example for floods, from a paper titled: “Current European flood-rich period exceptional compared with past 500 years”, Günter Blöschl et al 2020:

I haven’t been through the paper in detail to see if the title is backed up by the data.

We can see that the late 1700s could at that time have been described as “unprecentended in history”, whereas the late 1800s and early 1900s by comparison had very low floods. Then again, if you were in Spain the early 1800s might have been called the “worst ever”.

This demonstrates the problem of attribution.

Perhaps a recent flood is “the worst in history”, however history is defined. But that doesn’t automatically mean it can be attributed to burning fossil fuels. Climate scientists, at least when writing papers, are careful to avoid this claim.

It’s also true that some event might not be “the worst in history” and yet still be made worse (or better) as a result of global warming.

How do climate scientists make judgement calls on attribution? We’ll see more in the next article.

References

Drought under global warming: a review, Aiguo Dai, WIREs Climate Change 2010

Current European flood-rich period exceptional compared with past 500 years, Günter Blöschl et al, Nature 2020

Many times news articles or comments on news articles of floods and other extreme weather events point out anecdotally that extreme weather events are breaking all kinds of records and are usually attributed to anthropogenic causes. There is no understanding of how many thousands of towns, cities, regions, states, etc. that have kept weather records over centuries and so one would expect some kind of weather record would likely be broken somewhere in the country almost every day.